FTA Hacker

New member

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- Want to know how the job market is doing? Just look at the disability rolls.

The Great Recession has created a growing underclass of millions of unemployed who are unlikely to ever re-enter the labor force. Instead, they're relying on government support that they qualify for because of health issues.

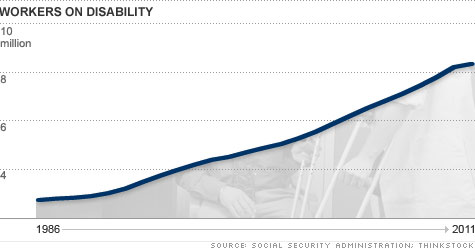

There are 8.3 million workers receiving disability payments, an increase of 1.2 million, or 17% from when the recession began, according to the Social Security Administration.

While it might seem like more people are trying to file illegitimate claims, experts say that's not the case. The percentage of claims being approved is about the same as in a good economy.

The real culprit: Workers with modest health problems are usually willing to take jobs when they can get them. But when they can't, they turn to the government. That's why the number of people who apply for -- and get approved for -- disability payments typically increases during bad economic times.

"There are people who, despite disability, are out there working when times are good," said Mark Lassiter, spokesman for the Social Security Administration, which runs the disability programs. "We've seen this increase in applications during other recessions. This jump is not due to fraud."

Hiring slows to crawl

And the rolls have been growing steadily for decades, since the government changed eligibility standards for the program in the early 1980s. Since then, the number of people receiving benefits has tripled.

Today there are only about 16 active workers for every person collecting disability, compared to more than twice that 20 years ago.

High costs

The program is disguising just how bad unemployment really is. If those 1.2 million new post-recession beneficiaries were still counted as unemployed, the national unemployment rate would be nearly a full percentage point higher than it currently is.

Another problem is that workers on disability often become dependent on the lifeline, and never return to work. Only 0.4% of workers in the program return to labor force each year.

Though the benefits are relatively modest -- only about $1,000 a month -- getting approved for disability can be a difficult process of appeals and hearings that typically lasts a year or more. Few who have qualified want to risk those benefits for a job that might not last.

"It's certainly not as good as earning wages," said Mark Duggan, an economics professor at University of Maryland, and a leading expert on the program. "But if they're on disability, they're anxious about saying, 'I'm going to try to go back to work and give up this sure thing.' There's a good chance you may not get back on. It's a long and uncertain process."

Because of the year-long delay from initial application to granting of benefits, there's still a large backlog of applicants filed in 2010 and earlier, still set to hit the rolls in the coming months. There are 734,666 cases pending as of April.

With disability rolls likely to grow, the program is squeezing government coffers, especially since disability recipients qualify for Medicare regardless of age.

"The program costs $200 billion per year when you add in cost of Medicare. It's basically almost $2,000 per household, per year," said David Autor, an economics professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Still, there is virtually no push for reforming disability in Washington, Autor said. Politicians don't want to be seen cutting benefits to the disabled, especially if it would drive up the reported unemployment rates.