Scammer

Banned

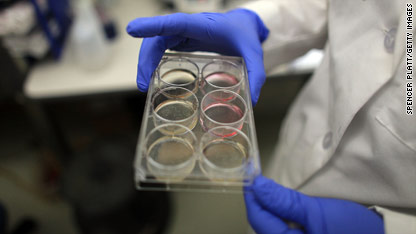

After years of animal trials, the first human has been injected with cells from human embryonic stem cells, according to Geron Corporation, the company which is sponsoring the controversial study.

"This is the first human embryonic stem cell trial in the world," Geron CEO Dr. Thomas Okarma tells CNN.

Geron is releasing very few details about the patient, but will say that the first person to receive cells derived from human embryonic stem cells was enrolled in the FDA-approved clinical trial at the Shepherd Center, a spinal cord and brain injury rehabilitation hospital in Atlanta, Georgia. This person was injected with the cells on Friday.

The FDA first approved this clinical trial in January 2009, but later required further research before the study could proceed. The FDA gave final approval in July of this year. This allowed the company to begin searching for the first patients who might qualify for this phase 1 clinical trial, which means scientists are trying to determine the safety of introducing these cells into a human.

To be eligible, patients have to have suffered what's called a complete thoracic spinal cord injury, which means no movement below the chest. While patients can still move their arms and breathe on their own, they are complete paraplegics; they have no bowel or bladder control and can't move their legs, Okarma explains.

The injury to the spinal cord would have to have occurred between the third and tenth thoracic vertebrae and the patient has to be injected with the stem cell therapy, called GRNOPC1, within seven to 14 days after the injury. "At the time of the injection, they [the cells] are programmed to make a new spinal cord – they insulate the damage [to the spinal cord]," says Okarma. The cells work just like they would if they were in the womb and building a spine in a fetus, Okarma explains.

Embryonic stem cells are only four to five days old and have the ability to turn into any cell in the body. But the cells that the patient receives aren't pure human embryonic stem cells anymore. The cells in the GRNOPC1 therapy have been coaxed into becoming early myelinated glial cells, a type of cell that insulates nerve cells.

"For every cell we inject, they become six to 10 cells in a few months," says Okarma. These cells can still divide some but will not become any type of cell other than glial cells, he explains.

The Geron CEO likens what these cells are doing to repairing a large electrical cable. If the outer layer is damaged and the wire is exposed, it causes a short-circuit and the cable doesn't work anymore. In the case of a spinal cord injury, these new stem-cell derived glial cells creep in between all the fibers and rewrap the nerve with myelin, which is like patching the cable. The goal is to permanently repair the damage that caused the paralysis from the spinal cord injury.

"We're not treating symptoms here – we're permanently regenerating tissue," says Okarma.

He adds that the goal of this stem cell therapy is to shift the outcome for someone who has just suffered a serious spinal cord injury, and go from a place where there's no hope for improvement to a situation where they can respond to physical therapy. "If we could do that, this would be a spectacular result," Okarma says.

The purpose of the clinical trial at this stage is to determine safety – to determine that there are no bad side effects or rejection caused by the therapy. Only eight to 10 patients are approved to be in the safety phase of this clinical trial, and patients with new spinal cord injuries are expected to be enrolled at about seven sites in the United States. Besides the Shepherd Center in Atlanta, Northwestern Medicine in Chicago, Illinois, also is recruiting patients.

The cells that are being injected into the patients are a product derived from stem cells that were harvested from leftover embryos from fertility clinics. Because this process destroys the embryo, this type of research has been very controversial. Consequently federal funding of this type of research has been equally controversial. However, Okarma has previously told CNN that "zero federal funds" were used for their human embryonic stem cell product.