Scammer

Banned

- Curtis Acosta's class on Latino literature opened on Monday with a poem:

"You are my other me," the high school students said in unison, reciting the words in Spanish and English. "If I do harm to you, I do harm to myself. If I love and respect you, I love and respect myself."

It's a simple message that took on new meaning here this week as the shooting of U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords and 18 others threatened to tear this desert town apart, drawing attention to divisions that Tucson might rather ignore.

Acosta's classroom is one example of those tensions. The state of Arizona has declared it and other classes in the Mexican-American studies program at Tucson High Magnet School illegal because they are "designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group." Other cultural studies programs, meanwhile, like those for African-Americans or Asians, have not been affected. (The class goes on while school officials negotiate with the state.)

Surrounded on all sides by ruddy mountains and only 60 miles from Arizona's border with Mexico, Tucson sees itself as an oasis of progressivism and diversity in a state that's gotten a national reputation for bigotry and anti-immigrant hate speech. It's the kind of place that hosts mariachi festivals, celebrates Cesar Chavez and asks cars to pull into parking spaces backward, for the safety of bicyclists.

But after the Democratic congresswoman was shot and six were killed Saturday during a political meet and greet at a supermarket on the northwest side of town, this place of golf courses, taquerias and cactuses started to look at itself anew -- examining not only the causes of the shooting but the borders residents put between each other.

A sharp-tongued sheriff seems to have set off the wave of introspection. "We have become the mecca for prejudice and bigotry," Pima County Sheriff Clarence Dupnik said of Arizona in a nationally televised press conference. Dupnik said this environment may have influenced an already disturbed shooter.

In interviews, some Tucson residents echoed those sentiments, saying tensions over race and immigration laws have created a divisive and dangerous atmosphere.

"Craziness takes its shape from what's in the air -- the ideas and discourse and rhetoric that's around," said Carole Edelsky, 73, a member of the "Tucson Raging Grannies" group, which supports the local Mexican-American studies classes by singing protest carols outside school board meetings.

"It takes someone really nuts to do that -- but the conditions were right."

Others reject that notion. They see the accused shooter, Jared Loughner, as mentally unstable. The event, they say, was an aberration -- not a reflection on this unique town, where the hot, dry air attracts arthritis patients seeking relief.

"It's the nicest place on Earth, as far as I'm concerned," said Mark Gardner, a New Yorker who spends the winter in Tucson because of the warm weather.

Gardner is like many who end up in this city of retirees, immigrants and transplants -- where chain stores are dressed up like pueblos and corduroy-textured cactuses line the roads, their stumpy hands outstretched like hitchhikers. He came to Tucson with romantic visions of the American Southwest.

What he found wasn't far off.

Southern Arizona holds that larger-than-life, cowboys-and-Indians, survival-against-the-elements charm for many of its residents.

Robert Goldman, a 62-year-old painter who moved to Tucson from Southern California, said it was at first difficult to appreciate the muted color palette of southern Arizona -- all the brown, yellow and tan. From a distance, the mountains here look as if they are so dry and devoid of life they could be blown over with a breeze.

But with time, he came to see this place's eccentric beauty. The dusty mountain ranges that surround Tucson turn vibrant shades of red and purple as the desert days wear on. The sky, which remains a lucid blue during the day, rarely disturbed by a cloud much less a shower, ignites in a heavenly fireworks show at dusk and dawn.

"It was almost like looking at the moon when I first got here," he said, staring up at the Santa Catalina Mountains from nearby a canvas on which he was painting a home with a red-tiled roof. "It took awhile to absorb the color and the light."

Like anything personal, it's easy to worry outsiders will misunderstand this place, which prides itself on being both big city and tight-knit town. Because of the shooting, Goldman said he fears outsiders will see Tucson as the Wild Wild West, a place of guns and hostilities -- a characterization he says is completely unfair. Others this week worried aloud that their town could become the next Oklahoma City, New York or Virginia Tech -- places known for tragic scars.

But they're holding out some hope.

Thousands cheered President Barack Obama's speech here Wednesday night, which called for a return to civil discourse after days of heated political rhetoric. "It's important for us to pause for a moment and make sure we're talking to everyone in a way that heals -- not in a way that wounds," Obama said.

Before the shootings, many in Tucson saw Arizona's big problems as located over the mountains -- either in Phoenix, the state capital and hub for politics and commerce, or along the Mexico border, which has been fraught with violence.

Residents point to state immigration reform, which was passed last year, as one example of this trend. Many in Tucson, including the county sheriff, oppose the law, which requires immigrants to carry registration documents and lets police demand those documents if they suspect someone may be in the U.S. illegally.

Dupnik, the sheriff, called the bill "racist." Many Tucsonans saw the law as originating outside their cozy bounds, choosing to associate it with Phoenix and Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio -- or "Sheriff Joe" -- who is known for imprisoning illegal immigrants in outdoor tent camps and making them wear pink underwear as a mark of shame.

For some, it felt like the immigration law created an atmosphere of fear in Tucson that didn't exist before. This is true for Michelle Rascon, a 21-year-old senior at the University of Arizona whose father was deported to Mexico in October. Now, she said, the shootings are "going to make people more fearful of going out and exercising their rights" to protest immigration laws.

"We live in the craziest place in the country right now."

Acosta's students are caught in the middle of these culture wars.

Some people say the Latino history and literature classes brainwash students into becoming anti-government activists who oppose immigration reform. The textbooks, syllabus and decorations have come under state scrutiny. Acosta's walls are lined with slogans, among them "We Are Human!" "We are American" "United Together En La Lucha!" (the struggle).

"It's a course that lends itself to indoctrination," said Jon Justice, a popular radio personality in town. The students "are in the position where they're not given all the facts, unfortunately," he said, noting the classes don't emphasize European history.

Acosta's class continues to meet as officials negotiate with the state about whether the program is in compliance with the new state law.

The students don't know quite how to explain it all.

"I think maybe it's just weird for them to see all of us trying to learn, too," Ally Attwood, a 17-year-old student who is half-Latino, said of people who support the ban. "We don't mean any harm. We all want to learn, and it just sucks we can't all get along."

There's no border fence running through the grid-based Tucson metro area, which, from the air, looks like a circuit board dropped into a sandbox. But as almost anyone here will tell you, and as census data shows, Latinos tend to live south of Broadway, where neighborhoods are called barrios and where political murals, tile work and corrugated-iron fencing could lead a confused visitor to think he had wandered into Mexico.

Whites, meanwhile, generally live to the north, where fenced-off retirement communities and lime-green golf courses climb the northern mountains. Up there, retirees take long afternoon strolls on canyon trails.

The occasional bobcat or rattlesnake is the only real security concern.

Drive 40 minutes up into those hills, to a place called Dove Mountain, and you'll find some people who avoid south Tucson unless it's absolutely necessary.

One of them is Armando Lazarte, a 64-year-old native of Peru who immigrated and became a citizen and lives in a subdivision of modern, adobe-style houses, the front yards decorated in pebbles (none of the yards in Tucson have grass, just gray rocks) and round cactuses that look like porcupine bowling balls. People up here tend to worry far more about immigration than those in the poorer barrios.

The Mexico border -- that's Tucson's biggest problem, Lazarte said.

"The agents should shoot to kill," he said of the Border Patrol. "I think they should bring some of the armed forces from Iraq or Afghanistan onto the border here."

Saturday's shooting is a sign things are getting wild in Tucson as well, according to some. Whoever committed the killings and assassination attempt, Lazarte said, should be punished without mercy. "In the past, in the West, they used to hang people," he said. "We should hang him, maybe. Or maybe shoot him a few times -- make him suffer his wounds."

Others are looking for preventive remedies.

Some point out that the alleged shooter was apparently alienated from Tucson society and suggest the area's rapid growth is partly to blame. Pima County, which includes Tucson, grew by 53 percent from 1990 to 2009, to a current population of about 1 million, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Some residents said the community should have done more to embrace the accused shooter. Others believe the tragedy shows the area's mental health services are inadequate, or its gun-control laws need re-examining.

Still others voice this notion: Tucson should just move on.

Robert Jones, an older man who wears a felt hat, has a wispy, white beard and lives on the fringe of the foothills, said it's best to focus on better times in Tucson history, as if talking too much about the shootings would ensure that they leave a scar on Arizona's Second City.

"It's not a good idea to think of the new negative things that have come up," he said.

Back downtown, where Tucson's modest skyline barely juts out above the toothy mountain horizon, the students in Acosta's class at Tucson High Magnet School struggled to work through the tragedy.

They asked questions: Who did this? Why? And why was everyone on TV talking about Tucson as a place of hate?

Acosta tried to encourage them.

"I'm the optimist and the hope guy," he said. "This country reacts really well to this stuff sometimes. I think it reminds us the best parts of who we are as a nation."

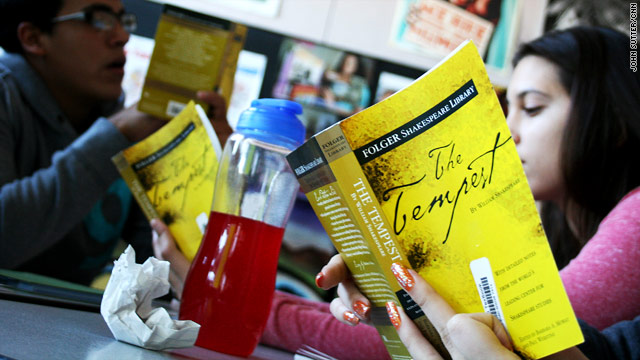

Then they went back to their studies, opening their copies of "The Tempest" by Shakespeare.

The class talked about a scene in which all of the characters are caught in a storm -- and they're reacting in various ways. Some make light of the situation, cracking inappropriate jokes. Others say they should be respectful and "sink with the King."

Acosta asked the students for their explanations.

"It seems like they've had a lack of communication," said a girl in purple boots. "There aren't connections. There's no trust," a boy wearing a black sweatshirt said. "He thinks she might not be that interested in what she's saying," offered another young man.

"Yeah, it seems they didn't have much in common," Acosta said.

In a divided town struggling to heal, the double meaning was hard to miss.